By Siddharth Dey

There are some terms which need explanation: right, injury, justification, claim, remedy, etc. These terms are intertwined with the basic elements of the Law of Torts.

So, we’ll deal with those terms along the basic elements themselves.

Elements of the Law of Torts

The Law of Torts has four basic components. These components are arranged in the order in which they come into play:

- Legal Right

- Wrongful Conduct

- Legal Injury

- Remedy

1. Legal Right

Without a legal right, you cannot have a successful claim in tort. In fact, the Law of Torts will not even apply. This makes it the most important element, because in its absence, the rest are useless.

This is because the presence of a legal right is the starting point of the Law of Torts. Be careful here that, although we are using “right” and “legal right” interchangeably, we aren’t talking about rights as such, such as an elderly man’s right to have a seat on a bus.

Such a ‘right’ exists only because it is a morally correct thing to do. However, no law obliges you to give your seat away to the elderly, and as a result the man has no legal right to that seat. A consumer, however, has a legal right to be compensated for defective goods, because that is provided for by the law.

The Law of Torts is only concerned with legal rights.

Lesson – a legal right is a right recognized by law.

“Which law?”

A law which is in force in the place you are in. To be in force means to be applicable when you go through with your actions.

“Where does this law come from?”

There are mainly two sources of law in India:

(i) Codified Law – any law of the present government, or any body authorized to make laws, which exists in written form. The Constitution, the different Acts of Parliament and Legislature, and different Rules, Regulation and Notifications are examples of codified law.

(ii) Case Law/Common Law – case laws are judgments which are delivered by the courts at the conclusion of any case. Although these judgments come in written form, they sit below the codified laws, since the task of the courts is simply to interpret the law and not to make the law – they are guided by these codified laws.

However, they can go against the codified law, only if that codified law itself contravenes a law superior to that, such as the Constitution; or fill up the loopholes in law where there are no legal provisions – however, they cannot create a new law in the process.

This practice has been taken from the UK, and countries following such a system are called common law countries. Others, which strictly follow the codified law, are called civil law countries

Sometimes, a legal right does not exist as such However, it is only because someone has a legal duty does that particular right exist. Such a right can only be enforced against the person who holds the corresponding duty.

For example, a drowning man does not have any right to be saved by a civilian. However, he only has a right to be saved by a life-guard. This is because, the life-guard has the duty to save that man. Therefore, he can make a claim only against the life-guard.

Lesson – legal rights and legal duties are correlated. If someone has a right, then someone else must have a duty, and vice-versa.

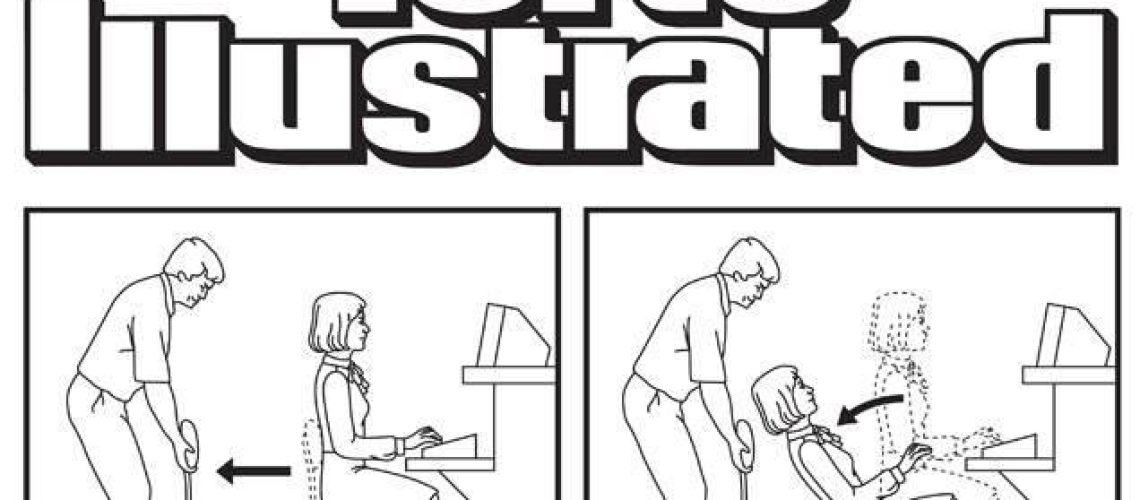

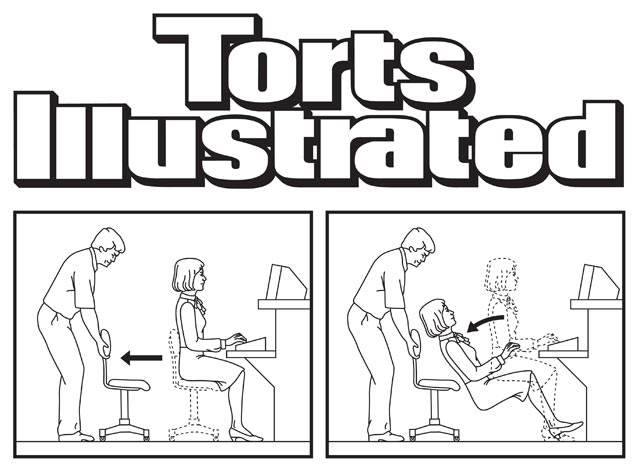

2. Wrongful Conduct

One person’s legal right is infringed or violated through another’s wrongful conduct.

The conduct is wrongful only because it violates the right. Meaning, the conduct is not necessarily wrong, but only becomes ‘wrong’ when it violates that right.

“Why so?”

Let’s consider that there is a wedding function taking place in your neighborhood. There’s bustling activity around your house, with cars coming in and going out. Then of course, there’s the music – which you absolutely detest!

It is, however, not deafening, and well within the legal limits. So, you take it in your stride.

However, if this was to continue past midnight, and you could not sleep peacefully, you would then magically possess this right to drag them to court; and, the court will agree with your philosophy – “if you don’t snooze, you lose”.

You will become infamous as one gigantic party-pooper, though.

Lesson – a wrongful conduct is not necessarily a ‘wrong’ or unlawful act. It is one which merely violates a person’s legal right.

“How does wrongful conduct occur?”

Wrongful conduct can take place in one of two ways:

(i) Commission, or

(ii) Omission

A commission (of a wrong) occurs when a person does something which s/he was not supposed to do. You can easily think of such a situation – for example, when you spill water on a friend’s laptop, which you had borrowed from him. You weren’t supposed to do that.

An omission (to not do a wrong) occurs when a person does not do something which s/he was supposed to do. For example, if you forget to turn of the lights when you leave your friend’s house to go on a vacation with him, and as a result he runs up a huge electricity bill, that’s omission. You should have done that!

When a wrongful conduct violates a legal right, it leads to a legal injury.

3. Legal Injury

Under the Law of Torts, ‘injury’ has been recognized under two principles.

(i) Injuria sine damnum – “injury without damage”.

(ii) Damnum sine injuria – “damage without injury”.

Now, in these principles two, the words, which look like synonyms, have been used in different contexts.

‘injuria’ means legal injury, while ‘damnum’ means actual injury/physical damage.

As we have already discussed which one really has significance, it is injuria sine damnum that the Law of Torts is bothered about.

“But, what about those cases which require damage too?”

I’ll clarify.

If you notice, the second principle basically says, ‘actual damage without legal injury’; however, you need legal injury to claim in Tort. Recall the example where the neighbour plays distasteful music, during usual hours of the day and within the legal limits.

Thus, the second principle only has ‘academic relevance’, as the judges call. It will feature nowhere in practical discussions on the Law of Torts.

Also, what the first principle does is barely mention the minimum requirement for a claim in tort, i.e., injuria. With a few exceptions, the presence of damnum is irrelevant for a claim as long as injuria is present.

For example, if a person is stopped from entering a polling booth without any justification, he automatically deserves a remedy because his right has been infringed. Whether his candidate of choice wins or does not win is immaterial.

Lesson: A claim can be made as soon as a legal injury is established. Actual damage is required only in exceptional cases.

[Note: I will refer to ‘legal injury’ as ‘injury’, and ‘actual injury/damage’ as ‘damage’, from hereon.]

4. Remedy

Once a legal injury has been established, the Court will provide you with a remedy.

This is based in the principle ubi jus, ibi remedium – “where there is a right, there is a remedy”.

The Law of Torts tries to bring the aggrieved person, or the claimant, back to the position which s/he would have been in had the wrongful conduct not occurred. This is done through a remedy.

In other words, a remedy tries to revert the damage done.

There are broadly three types of remedies:

(i) Damages

It is the most popular form of remedy. It is simply a monetary estimate of your injury, based on its nature and severity. Therefore, it can be awarded in any case as a remedy, since all injuries can be estimated in one way or the other.

The damages awarded are unliquidated. Meaning, that they are not pre-decided between the parties, and has to be estimated by the court while awarding it. There is no one-size-fits-all formula, and the damage has to be assessed on a case-to-case basis, and damages are decided accordingly.

“Damage v. Damages – what’s the catch?”

Why the extra ‘s’? ‘Damage’ means injury, which cannot be quantified to a specific number. It can only be estimated. However, a monetary sum, or ‘damages’ can be quantified.

It’s not at all a case of being singular & plural forms!

(ii) Injunction

An Injunction is a court’s order to stop a person from doing a tortuous act. This is usually when the tortious act is continuous in nature, or occurs periodically, in order to put a stop to any further occurrence. Therefore, it cannot be given out as a remedy in all cases

For example, if your neighbour plays loud music every night, there is no point in awarding you damages only. Your neighbour can only go and play it again – there’s no one stopping him/her from that.

That’s where the court will issue an order for injunction, asking him/her to stop playing the music at night. The injunction can be partial or total – s/he may be barred from playing music at all hours, too!

(iii) Restitution

Restitution remedies a case where there is actual or physical damage.

The court orders for restitution when a thing or object has to be restored by the tortfeasor to either the condition:

(a) as it was when s/he damaged it.

(b) or a condition better than that.

So, if your friend accidentally breaks your phone’s screen, you should probably be getting a new phone in return. Unless, your screen was already broken, and was holding on for dear life with a piece of sellotape. Then you simply…put more sellotapes!

Of course, restitution only works if the object can be restored. For example, an antique from the Harappan Civilization is unlikely to be restored if damaged. Thus, restitution also finds limited usage in remedy.

1 thought on “<b>CLAT Legal Reasoning</b>: Law of Torts & its Elements”

amazing

basics were taught comprehensively

thank you